Grand Duchess Elizabeth Fyodorovna, 1904

Deeds and letters are those things that in the best possible way show what kind of person someone is. The letters of Grand Duchess Elizabeth reveal the principles which laid the foundation of her life and relationships with people around her. These letters help us understand the reasons why the high-society beauty became a saint in her lifetime.

In Russia, Elizabeth Feodorovna was renowned not only as “Europe’s most beautiful princess”, a sister of the empress and wife of the tsar’s uncle. The country knew her as founder of the Martha and Mary Convent, a convent of a new type.

In 1918 Elizabeth Fyodorovna was on Lenin’s order thrown to an abandoned mine, hidden in an impenetrable forest, so that no one could ever find her.

Elizabeth Fyodorovna was very fond of nature. She could spend hours walking, without ladies-in-waiting, disregarding he formal rules of etiquette.

On faith: “Visual attributes remind me of the inner part of faith”

In marrying Grand Duke Sergei Alexandrovich, Elizabeth Fyodorovna was free to remain Lutheran, as she had been by birth. According to the rules of that time, conversion was only necessary for those who married heirs of the Russian throne. However, on the seventh year of marriage she decided to adopt the Orthodox faith. She made this step of her own volition, not for her husband.

St. Elizabeth with her family: father, Louis IV, Grand Duke of Hesse and Rhine; sister Alix (future empress Alexandra Fyodorovna), princess Elizabeth, elder sister Victoria and brother Ernst Louis.

A portion from a letter to her father, Louis IV, Grand Duke of Hesse and Rhine (January 1, 1891):

I have come to this decision [to convert to the Orthodoxy] only due to my deep faith. I feel that I should stand before God with a pure and faithful heart. How easy it would for everything to remain as it is now, and how fake and hypocritical at the same time! How can I lie to everyone, pretend being a Protestant, and showing it by my appearance, while my soul has already embraced the Orthodox faith? After I’ve spent six years in this country and already “found” religion, I’ve been thinking, thinking long and hard, about everything.

To my surprise, I almost fully understand texts and services in Slavonic, despite never learning the language. You say that I’m enchanted by the splendor of the churches. But I don’t think you’re right. I’m impressed neither by anything visual nor by the service itself, but the foundation of faith. Visual attributes remind me of the inner part of it.

About the revolution: “I would rather be killed by a first accidental shot, than stay here doing nothing”

From a letter to V. F. Dzhunkovsky, adjutant of Grand Duke Sergei Alexandrovich (1905):

The revolution can’t finish soon, it may only sharply deteriorate and become something chronic, which is bound to happen. It is my duty to help poor victims of the rebellion. I would rather be killed by a first accidental shot, than stay here doing nothing.

The revolution of 1905-1907, barricades in Ekaterininsky lane (Moscow)

From a letter to Tsar Nicholas II (December 29, 1916):

Huge waves are going to crash down upon us soon <…> All the classes, both lower and higher ones, even those who are now at the war, are at the end of their rope! <…> What other tragedies can strike us? What other miseries are in store for us?

Sergei Alexandrovich and Elizabeth Fyodorovna, 1892

About forgiving enemies: “Knowing the generous heart of my late husband, I forgive you.”

Social-Revolutionary terrorist Ivan Kaliaev, who in 1905 assassinated Sergei Alexandrovich

In 1905 St. Elizabeth’s husband, the Moscow governor-general Grand Duke Sergei Alexandrovich was assassinated with a bomb by Social-Revolutionary terrorist Ivan Kaliaev. When Elizabeth Feodorovna heard the explosion, detonated not far from their house, she rushed outside to collect the dismembered remains. Then she spent hours in prayer. Some time later she petitioned the emperor to have mercy on the assassin. She visited Kaliaev in prison. Leaving the Gospel, she said she had forgiven him.

From a cipher telegram, written by head of the Governing Senate E. B. Vasilyev (February 8, 1905):

The Grand Duchess met the assassin in the office of Pyatnitsky unit at 8 o’clock in the evening February 7. To the question of who she was, the Grand Duchess said, “I’m the wife of the man you have killed. Tell me, why did you do this?” The defendant rose to answer, “I did what I had been charged with. It’s the fault of the existing regime.” Full of mercy, the Grand Duchess said, “Knowing the generous heart of my late husband, I forgive you”, and blessed the assassin. Then she stayed alone with the criminal for about twenty minutes. When the meeting was over, he said to the officer, “The Grand Duchess is kind, and you all are cruel.”

From a letter to empress Maria Feodorovna (March 8, 1905):

A small white cross, installed at the place of his death, was a consolation for me. The following evening I could go there to pray; as I closed my eyes I saw this pure symbol of Christ right in front of me. It’s a great mercy. After that evening, every time I go to bed I say, “Good night!”. I pray, and a sense of peace imbues both my heart and soul.

On prayer: “I don’t know how to pray well.”

From a letter to Duchess Z. N. Yusupova (June 23, 1908):

Praying by the relics of St. Alexey of Moscow made me quiet and peaceful both in heart and soul. I wish you had a chance to come to the relics, venerate them and pray, so that peace could embrace you, and remain in you. Hardly did I pray… Alas, I don’t know how to pray well. I fell down, literally fell down before them, like a child to her mother’s breast. I prayed for nothing as my heart was full of peace, I realized that I was standing close to the saint, on whom I could rely, and with whom I am not alone.

Handmade embroidery of Elizabeth Feodorovna. The image of the sisters Martha and Mary signifies the path of service to others, chosen by the Grand Duchess: good deeds and prayer.

About monastic vows: “I took it as the path of salvation, not a cross”

Four years after her husband’s death, Elizabeth Feodorovna sold all her jewelry and possessions, and the part, belonging to the Romanovs, she gave back to them. With the proceeds she opened the Martha and Mary Convent.

Elizabeth Fyodorovna as a sister of mercy

From a letter to Nicholas II (March 26, April 18, 1909)

My new life starts in two weeks, life blessed in the church. It seems I’m leaving my past behind, with its sins and mistakes, hoping for loftier goals and purer existence. <…> For me, taking monastic vows is something more serious than marriage is for a young woman. I’m becoming engaged to Christ and his service. I give everything I have to him and my neighbor.

A view of the Martha and Mary Convent, 1900-s

From a telegram and a letter to Saint-Petersburg Theological Academy professor A. A. Dmitrievsky (1911):

Some people doubt whether I decided to make this decision by myself, without anyone’s influence. Many think that I have taken an unbearable cross upon myself, and I shall either abandon it or fall under the weight of it. However, I don’t take it as a cross, but as a path full of light, pointed by God after Sergei’s death; I have seen the flashes of this light in my soul for a long time. It’s not a transition; it’s something that has been arising inside of me, taking shape. <…> I was absolutely astonished to see a fight brake out. They wanted to hinder me, daunt me by suffering. They did it all with love and of best intentions, but without understanding my character.

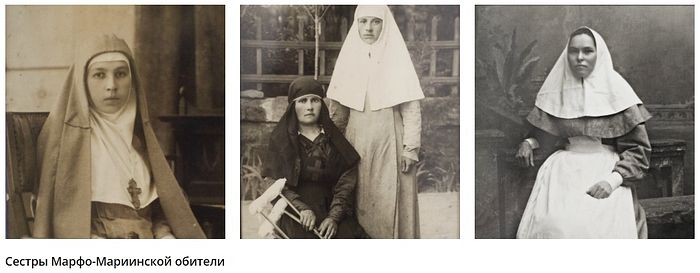

The Martha and Mary sisters

About relations with people: “I have to do the same things as they do”

From a letter to E. N. Narishkina (1910):

You may like many others say to me: “Stay in your palace as a widow and do your good works ‘from-above’.” If I want others to follow my principles I have to do things as they do, go through the same troubles. I have to be strong enough to comfort them and inspire by my own example. I’m neither intelligent nor gifted, I have nothing but love for Christ, but I’m weak. We can only express our love for him and our faithfulness by comforting people around us. Doing this we can dedicate our life to him.

The sisters with a group the First World War soldiers

About treating ourselves: “We should move forward slowly enough to think we’re standing still”

From a letter to Tsar Nicholas II (March 26, 1910):

The higher we try to reach, the more strict we are with ourselves, the more shrewdly the devil acts to make us blind to the light of truth. <…> We should move forward slowly enough to think we’re standing still. We must not look down on anyone, we should consider ourselves the most wicked. I’ve always believed this idea has a touch of falsehood—to consider yourself the most wicked. To the contrary, this is what we should strive for; everything is possible with the help of God.

Why does God allow us to suffer?

From a letter to countess A. A. Oslufyeva (1916):

I’m not thrilled, my friend. I’m just sure that God who punishes us is the same God who loves us. Lately, I’ve often been reading the Gospel; if we try to recognize the great sacrifice of God the Father, Who gave his own Son to death and resurrected him, then we shall feel the presence of the Holy Spirit, lightening our life. Then joy seems eternal even at times when our poor human hearts, our tiny mind goes through troubles that seem tremendous.

About Rasputin: “This is a man who lives several lives”

Elizabeth Fyodorovna was utterly critical of her sister’s, empress Alexandra Fyodorovna’s, trust in Georgy Rasputin. She believed that Rasputin’s dark influence made the Royal family “blind; this caused the negative attitude towards the Romanov family and the country.”

From a letter to Tsar Nicholas II (February 4, 1912):

I could clearly see that what was coming; various people from the whole country were asking me to warn you about him. He was a man living several lives, as those who knew him claimed. They said you would never see his real self; he would be hiding the part which any honest man would find horrible.

Elizabeth Fyodorovna repeatedly tried to warn Tsar Nicholas of Rasputin’s negative influence on the Royal family. Unfortunately, those attempts were fruitless.

From a letter to Tsar Nicholas II (December 29, 1916):

I spent ten days praying for you, for the army, for the country and all its ministers, for all those who suffer mentally and physically; the name of that poor [G. Rasputin] was also in my commemoration list—to pray that God enlightens him... Then I come back home to know that Felix has killed him, my little Felix, whom I remember as a child, who had always been afraid to kill any creature and didn’t want to be in the military lest he spill anyone’s blood.

<…> I assume that no one dared to tell you that people in the streets, and not only in the streets, were kissing each other with joy as if it were Paschal night; in theaters they were singing hymns. The whole country was united by an outburst of happiness; the black wall separating us from our country has finally been demolished. We shall soon see this outburst as it is. A wave of compassionate love for you touched every heart. I hope you will learn about this love, that you will feel it; but, please, don’t miss this great moment. The thunder is still crashing, and the peals can be heard in the distance.

Elizabeth Feodorovna not long before her death

About death: “I don’t like this word”

From letters to Grand Duke Pavel Alexandrovich (March 31, 1905) and Duchess Z. N. Yusupova (July 1, 1908):

Death is a separation after all. I don’t like this word; I think that those who pass away make a way for us, and our prayers help them clear the path will have to go.

Till the last minute

From the memoirs of Nun Nadezhda, Zinaida Brenner in the world, (1890-1983), who once lived in the Martha and Mary Convent:

To the question of what virtue Elizabeth Feodorovna appreciated most, mother Nadezhda said, “It was mercy, and she appreciated any manifestation of it. She was merciful till the very last minute of her life.”

From the letter of Metropolitan Anastasius (Gribanovsky, ROCOR), concerning the “Loving memory of Grand Duchess Elizabeth Fyodorovna” (July 18, 1918, Jerusalem):

The results of excavations carried out later show that till the last minute she [Elizabeth Feodorovna] was trying to help the Grand Dukes, wounded when falling to the mine (she bandaged the wounds.) And the local peasants, who watched the execution from a distance, could for a long time hear mysterious singing, which wafted from the ground.

Memorial cross at the place of St. Elizabeth’ death

Zoya Zhalnina

Translation by Maria Litzman

Miloserdie.ru

10/11/2018

SOURCE

Δεν υπάρχουν σχόλια:

Δημοσίευση σχολίου