1. Preaching Orthodoxy to the Ends of the Earth

At the end of His time on earth, Our Lord Jesus Christc commanded His Apostles and disciples, saying, Go ye therefore, and teach all nations (Mt. 28:19). At the feast of Pentecost this preaching to all peoples was manifest in the spiritual gift of “tongues,” when the Apostles’ words were miraculously heard by their listeners in their own languages.Since that time the “gift of tongues” has been extremely rare, but has been replaced by the efforts of Orthodox missionaries to study the language and culture of the people they preach to, presenting the Gospel to them in their native tongue andin a cultural context, yet without compromising the Faith.

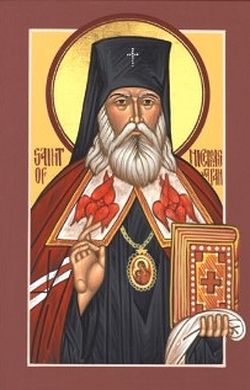

Such missionaries have often been called “equals-to-the-apostles” by the Orthodox Church, thatis, those who labored with the zeal and in the mannerof the first Apostles. Well known among such saints are Sts. Cyril and Methodius, the ninth-century evangelizers of the Slavic peoples. A more recent example of this type of saint is St. Nicholas (Kasatkin), who brought the light of Orthodoxy to the people of Japan.

2.St. Nicholas’ Early Years (1836–1860)

Ivan Dmitrievich Kasatkin was born on August 1, 1836, in the village of Beryozha of the Belsk district in the Smolensk region of Russia. His father, Deacon Dmitry Kasatkin, had four children: Gabriel (who died in early childhood), Olga, Ivan, and Basil. When Ivan was five, his mother reposed and his older sister Olga, whose husband served as a deaconin a rural church, began taking care of the children. The future archbishop and saint studied in the Belsk Ecclesiastical Primary School, then in theSmolensk Seminary. After graduating at the top of his class, he received a state scholarship to enter the St. Petersburg Theological Academyin 1856.

In the spring of 1860, an announcement inviting a graduate to serve as chief priest of the Russian Embassy churchin Japan was posted at the academy. Having calmly read the announcement, the young man went to the evening service, where he experienced a sudden desire to go to Japan. He completed the application with the intent of serving as a monk rather than as a married priest, and easily gained the position.

On June 21, 1860, Ivan Kasatkin was tonsured a monk with the name Nicholas.He was ordained a hierodeacon on June 29, and a hieromonk on the following day. He then set out on the long journey toJapan. Hieromonk Nicholas spent the winter of 1860–61in Nikolaevskon the river Amur, where Bishop Innocent (Veniaminov) of Kamchatka, the future saint, enlightener of Siberia and Alaska, and Metropolitan of Moscow, instructed the young missionary. St. Nicholasremembered these talks with Bishop Innocent for the rest of his life. It was St. Innocent who kindled the young missionary’s inspiration to study the language and culture of Japan.

3. Preparing to Spread the Gospel (1861–1873)

Aftera year’s journey, in June1861 Hieromonk Nicholas arrived at the port of Hakodate. At the time of his arrival the medieval charter of 1614, which entirely prohibited Christianity, was still in force. Although later, in 1873,a civil law would allow freedom of religion, obstacles to the propagation of the Faith continued t o exist, and persecutions, especially in rural areas, continued for a longtime.

St. Nicholas began his earnest study of the country’s language, culture and history. “He sometimes strolled around the streets of Hakodate, listening to theordinary people and professional storytellers. He made the acquaintance of leading Buddhist priests and listened to their sermons…. Hieromonk Nicholas spent fourteen hours a day over the course of seven years studying every aspect of Japan…. As a result of his relentless study of the Japanese language, Hieromonk Nicholas eventually acquired the knowledge of several thousand Chinese characters, giving him access to materials printed by the Orthodox mission in Peking, where Joseph Goshkevich[1] had spent almost ten years. This allowed Nicholas to study Chinese texts of the Old and New Testaments, as well as some of the liturgical books.”[2] Bishop Seraphim (Sigrist) of Sendai and the East (now retired) further describes St. Nicholas’ zeal in preparing for his missionary labors: “The story is told that in his early days of studying Japanese, Fr. Nicholas (then a priest in Hakodate) would go with the Japanese children to school and sit in theback and learn as best he could with them. Indeed, atone point the perplexed teachers put up a sign at the door: ‘The bearded foreigner is not allowed.’”[3]

While stillin Hakodate St. Nicholas was well aware of the massive tasks that lay before him. In 1869 he wrote: “One can draw the conclusion that at least the harvest truly is bountiful in Japan in the near future, but there are no laborers on ourside, not even one, if not counting my own personal activity…. Just translating the New Testament … will take at least two years of dedicated work. Then, the translation of the Old Testamentis necessary too. Even in the smallest [Orthodox] congregation the services will have to be held in Japanese. What about the other books, such as sacred history, Church history, liturgics, and theology? All of those are necessities as well, and must be translated into Japanese.And no one knows if a foreigner could master Japanese sufficiently to write it at least half as easily as he normally writes in his own language.”[4]

Aftera few years of intense study, Fr. Nicholas converted a samurai, the son-in-law of a Shinto priest, along with two others. (This samurai was the future Orthodox priest Paul Sawabe. The saint did not attempt to convert large numbers of people, but strove instead to make sure that those he did convert were strong in the Faith. These first converts then assisted him, and he soon had a group of fifteen Christians.

In late1869 Hieromonk Nicholas came to St. Petersburg to report on his work to the Synod.A decision was made “to setup a special Russian Ecclesiastical Mission to preach God’s word among pagans.” Fr Nicholaswas promoted to the rank of archimandrite and appointed head of the Mission.

4. Beginning Labors inTokyo (1873–1885)

In 1873,after St. Nicholashad been laboring for twelve years, conditions began to improve. Thanks to the forward-looking policies of Emperor Meiji, the Japanese government issued a new civil law granting religious tolerance. The Missionwas then moved from Hakodate to Tokyo, the new imperial capital, where the numberof Orthodox faithful soon reached a thousand.

St. Nicholas held the work of translation to be one of the most important activities he could accomplish in helping to lay the foundations of the Orthodox Missionin Japan. He once said: “Translation is the core of missionary work. Nowadays the work of a mission in general,in any country, cannot be limited to oral preaching alone…. In Japan, where people like reading and respect the printed word so much, we must first of all provide the faithful and those who are about to be baptized with books printed in their mother tongue, by allmeans well-written and neatly and cheaply published…. The printed word must be the soul of the mission.”[5]

In spreading Orthodoxy to the Japanese, St. Nicholas knew it would be especially effective for thenew Japanese Christians to bring the Faith to their own people themselves. Thus, during the 1870s he began to encourage those who had been members of the Church for some time, and who had received lengthy instruction, to travel throughout Japan and introduce the Faith to their countrymen. These catechists, like new apostles, would preach and then, if new believers were willing, would hold services in theirhomes and even use those homes as “stations” from which to teach the Faith. Ordained priests or even St. Nicholashimself would visit these missions when possible, to serve the sacraments and further strengthen the faithful. Over 250 missions were founded in this manner during St. Nicholas’ lifetime.

From the time ofhis arrival St. Nicholas lived nearly all his life in Japan, briefly returning to Russia only twice: from 1869 to1870 to request the establishment of the Russian Ecclesiastical Missionin Japan, and from1879 to1880 to be consecrated bishop of the growing mission and to collect funds for its needs. Each time he was particularly eager to go back home to Japan, to continue his work.

5. Labors as a Bishop (1885–1912)

In 1875 the first Japanese Orthodox priest, Fr. Paul Sawabe, was ordained. St. Nicholas founded schools for the instruction of catechumens and the faithful, and in 1878he opened a theologica college for the training of the Japanese clergy. Besides theological courses, Japanese, Chinese and Russian were taught there to prepare for the eventual translation of all the Holy Scriptures as wellas other essential texts. In 1880 St. Nicholas was consecrated as the first bishop ofJapan, and by 1884 he had begun the construction of a beautiful cathedral in Tokyo. It was completed and consecrated in 1891, and dedicated to Christ’s Holy Resurrection. However, it soon became known among the people as “Nikolai-do” (“Nicholas’ house”), a name it bears to this day. While St. Nicholas handed down the traditions and liturgical customs of the Russian Church to his flock, he nevertheless strove to form a truly Japanese Church, in both language and identity.

St. Nicholas’ personal example of love and respect for the Japanese people and their history, language,and customs left a good impression on the Japanese authorities and helped contribute to the growth of the Orthodox mission. St. Nicholas’ fluency in Japanese led to his being occasionally called upon to be present during official government meetings between Japanese and Russian representatives.

The Russo-Japanese War of 1904–5tested St. Nicholas and the Orthodox Christians in Japan. Using great discernment, he allowed his clergy to hold services of supplication for a Japanese victory, while not taking part in such services himself. Although he was offered protection by the Russians, he declined this, preferring to remain with his flock.

In 1906 Bishop Nicholas was raised to the rank of archbishop, and the faithful in Japan celebrated his twenty-fifth anniversary as their bishop.

In 1908 St. Nicholas’ future successor, Bishop Sergius (Tikhomirov), arrived in Tokyo. Bishop Sergius headed the Japanese Orthodox church from 1912 to1940. In 1912,the last year of St. Nicholas’ life, there were 33,000 faithful in 266 congregationsin Japan. There were 175 churches and eight cathedrals, served by forty Japanese priests and deacons.

6. The Reposeof St. Nicholas

Archbishop Nicholas began to suffer from heart diseasein 1910.His illness increased to the point thatin January 1912he was hospitalized. Oneevening Bishop Sergius entered the hospital to see his teacher. Later, he described what he saw: “A low table stands by the window of the room. Japanese manuscripts, an ink-bottle, and a brush are laid upon it,and before [his Eminence] is a Slavonic Triodion. [Paul] Nakai reads a Japanesetranslation [and] the archbishop follows his reading, looking into another notebook. At times they stop and insert a comma…. Could one have said that this was an old man, sentenced to inevitable death?”[6]

Gifted with an energetic and driven disposition, St. Nicholas always retained a humble perspective on his labors to the end of his days, once saying, “I am nothing more than a matchstick with which a candleis lit. Afterwards, the match goes out and is thrown on the ground as good for nothing.”[7]

On February 3/16,at7:15pm, His Eminence Nicholas, the Archbishop of Japan, reposed. The next day all Japan knew of his death.

Bishop Sergius wrote: “Tokyo Christians started making their way, one after another, to the Mission; Christians of other confessions expressed their condolences.… Those who had not yet accepted Christ’s teaching hurried to the Mission to bow or to leave a visiting card. They were not only ordinary citizens, but princes, counts, viscounts, barons, ministers and non-civil servants as well….

“But the highest honor rendered by Japan to Archbishop Nicholas was the fact that the Emperor of Japan [Meiji] himself … sent a magnificent and colossal wreath of natural flowers forthe archbishop’s coffin, and he did not do this in secret!... Accepting the wreath and replying with words of gratitude, we placed the wreath at St. Nicholas’ head.… The Emperor ofJapan himself crowned the head of God’s hierarch with flowers of victory!... There were two characters inside the wreath: ‘On-Shi,’ i.e., ‘the Highest Gift’… All the Japanese saw these two characters, read them, and reverently bowed their heads before the wreath!…

“Having started with a tremendous risk to his life, Archbishop Nicholas completed his activity in Japan with approval from the high Throne.”[8]

7. From 1912 to the Present Day

The years that followed St. Nicholas’ repose were marked by great difficulties and trials for the Japanese Orthodox Church. It not only had to face the challenges of being cut off from the Church in Russia due to the Bolshevik Revolution, which led to financial hardships, but also had to deal with the difficult years culminating in the Second World War and its aftermath. From 1945 to 1970 the Japanese Church was under the administration of the American Metropolia of the Russian Church (now the Orthodox Church in America).On April10, 1970, the Japanese Church was granted autonomy by the Russian Orthodox Church, and Archbishop Nicholas was glorified as a saint.

Throughout its almost hundred-year history since the saint’s death, the Japanese Church has kept the canons and traditions of Orthodox celebration that were established by St. Nicholas. The 266 parishes of the time of St. Nicholas have united to form the current 69 congregations of Japanese Orthodox Church. As in apostolic times, the Church in Japan finds itself a tiny minority in a society which has not yet received the light of Christ, a little flock (Luke 12:32) in the midst of one of the most materially prosperous nations on earth. But that small seed may yet grow into a great tree (cf. Mt. 13:31), for as St. Nicholas proclaimed, the harvest is truly bountiful (Luke 10:2).

From the St. Herman Calendar, 2011, St. Herman Press.

St. Herman of Alaska Brotherhood

with special thanks to Galina Besstremyannaya

2/17/2012

[1] Joseph Goshkevich (1814–1875)wasa Russianorientalist who initially worked in China and laterbecamethe first Russian diplomatic representative to Japan. [2]Bartholomew,D., “Hieromonk Nikolai (Kasatkin): The Hakodate Years: 1861–1869 & 1871,” Divine Ascent, no.6 (2000), p. 27.

[3]Bishop Seraphim (Sigrist), “Letter of Salutation,” Divine Ascent, no. 6 (2000), p. 14.

[4]Alexei Potapov, “St. Nikolai’s Translating and Publishing Work,” Divine Ascent, no. 6 (2000), p. 85

[5]Alexei Potapov, “St. Nikolai’s Translating and Publishing Work,” p.83.

[6] Metropolitan Sergius (Tikhomirov), “In Memory of His Eminence Nicholas, Archbishop of Japan, on the Anniversary of His Repose, February 3, 1912,” Christian Readings, January 1913, p. 40 (in Russian).

[7] St. Nicholas of Japan: Brief Biography and Journals, 1870-1911 (St. Petersburg: Bibliopolis, 2007), p 400 (in Russian).

[8] Metropolitan Sergius (Tikhomirov), “In Memory of His Eminence Nicholas,” pp66, 73.

source

Δεν υπάρχουν σχόλια:

Δημοσίευση σχολίου