Monk Nicodemus (Jones)

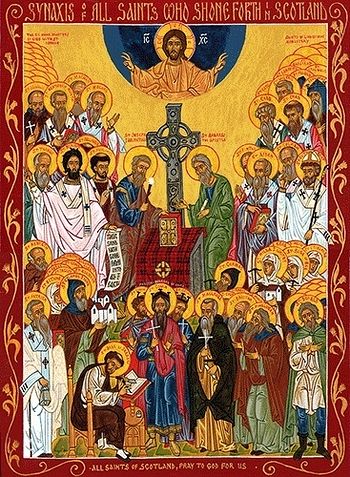

Synaxis of the Saints of Scotland. Photo: ancientfaith.com

1. St. Ninian and the beginning of Christianity in Scotland

The British Isles received Christianity from the very beginning, but the Christian influence was primarily limited to the area along their southern and southeastern shores, that is, those lands which had been colonized by the Romans. Those lands that had not been colonized, such as Scotland and Ireland, received Christianity a few centuries later.

The first of the great missionaries to Scotland was the fifth-century British bishop St. Ninian (Sept. 16, 432). He was spiritually and monastically formed by St. Martin of Tours (Nov. 11, 397) in the monastery of Marmoutier in Gaul (France) before heading to the southwest shore of Scotland. St. Bede of Northumbria (May 27, 735) wrote of him: “The southern Picts are said to have abandoned the errors of idolatry long before this date and accepted the true Faith through the preaching of Bishop Ninian, a most reverend and holy man ofBritish race, who had been regularly instructed in the mysteries of the Christian Faith in Rome. Ninian’s own episcopal see, named after St. Martin and famous for its stately church, is now held by the English, and it is here that his body and those of many saints now lie at rest. This place is known as Candida Casa, the White House [Whithorn], because he built the church of stone, which was unusual among the Britons” (St. Bede, Ecclesiastical History of the English People).

Before his death St. Ninian trained many great and holy men, one of the greatest of whom was St. Enda of Aran (March 23, 530). After spending some time at Whithorn, St. Enda returned to his native Irelan and founded a monastery on the Aran Islands. Many of his disciples went on to found monasteries I Ireland as well, such as the angelic St. Kieran of Clonmacnois (Sept. 9, 545) and St. Finian of Clonard (Dec. 12, 549).

St. Finian’s Clonard monastery in Ireland was to spawn the “Twelve Apostles of Ireland,” among whom were many who would later go into voluntary exile for the sake of Christ among the islands of Scotland and beyond, simultaneously bringing the Gospel to her peoples. In this way, the Gospel talent that St. Ninian invested in St. Enda was returned to Scotland a hundredfold through St. Finian’s disciples, such as Sts. Brendan of Clonfert, “the Voyager” (May 16, 577), Comgall of Bangor (May 11, 603) and, of course, the great Columba of Iona (June 9, 597).

2. The white martyrdom of the Irish monks

Christianity had already entered quietly into Ireland in the late fourth century. Yet when St. Patrick (March 17, 451) and St. Enda of Aran brought monasticism to Ireland, Christianity spread across the country like a forest fire raging out of control. The passions of the fierce-tempered, beauty-loving Irish soul were redirected in their proper direction – the heavenly kingdom. This resulted in hundreds of thousands of spiritual warriors who strove to “seize the kingdom of heaven with violence.” And truly they did “take it by force” (cf. Matthew 11:17).

By the beginning of the sixth century almost all of Ireland was ablaze with Christianity, and sparks were issuing forth from the blaze. These sparks were initially those rnonks who went on “pilgrimage for Christ,” who consciously abandoned their homeland and sailed off to the north and beyond in search of a “desert in the ocean.” The Irish monks called this desired location “the place of one’s resurrection” – that is, the place where God had called them to labor, to die and be buried, and from which to arise at the Last Judgment.

The Irish loved their country in a way that few can understand today, and for them to leave their beloved homeland produced a constant agony similiar to what unwilling immigrants to America felt. For an Irishman to consciously abandon his homeland for the sake of Christ we akin to a long, drawn-out martyrdom. A late seventh-century Irish monastic document known as “The Homily of Cambrai” does, in fact, describe such a sacrifice as “white martyrdom”:

“There are in fact three kinds of martyrdom, which we may regard as types of [carrying one’s] cross in human eyes: namely, white martyrdom, green martyrdom, and red martyrdom.

“A person undergoes white martyrdom when he leaves all for the sake of Christ, even though this means fasting, hunger, and hard work.

“Green martyrdom is attributed to someone who through them – that is fasting and work – is freed of his desires, or undergoes travail in sorrow and penance.

“Red martyrdom is to be found in the sufferings of cross of death for Christ’s sake, as was the way with the apostles, because of the persecution of the wicked, and while preaching the truths of God.

“These three lands of martyrdom are to be found in those sinful persons who are truly repentant, who abandon their self-will, and who shed their blood in fasting and in manual labor for the sake of Christ.”

3. The lure of the desert

The Hermit's Cell. Photo: colmcille.org

Among the Irish monks who sailed to the north there were great missionaries, but most of them were in search of an abandoned, unknown, remote land where they could live a solitary life devoid fall contact with others and be alone with God. The first stops that these monks made in their eager northward sea journeys were the west coasts of Scotland and especially the islands further to the west off these coasts. These “Western Isles” of Scotland, also known as the Hebrides, came to be filled with these Irish ascetics and anchorites. While some of the Irish monks continued on their voyages north, others settled deeper into the country in search of solitude. And truly, even to the modern Orthodox pilgrim’s eyes, the wild, harsh, rugged, lonely, and beautiful mountains and cliffs, which tightly nestle bright green valleys and deep blue lochs between their highland peaks, are ideal locations for monastic quietude and ascetic endeavor: where one can seek out and cultivate the seed of grace planted within one’s heart at holy Baptism – the Kingdom of God (cf. Luke 17:21).

Nevertheless, it was the multitudes of uncharted, uninhabited islands far off in the Atlantic Ocean that exerted the stronger pull on the Irish monks throughout the centuries, drawing them further and further northward, away from their homeland. Over the next five centuries the Irish monastic sailors spread abroad to the north, to the east (to the Scandanavian countries and northern Russia) and to the west (to Iceland, to Greenland, and even to North America).

4. The monastic life of Scotland’s missionaries

The Teampull Mholuaidh or St Moluag's church at Eoropie, Isle of Lewis, Scotland. Photo: wikipedia

One writer has written: “To capture the atmosphere of the early Celtic missionaries, travel north to Ness on the Butt of Lewis [the northernmost island of the Outer Hebrides]. At Eorpaidh Tempull Mholuaidh is a Norse Christian foundation on the site of a Celtic Christian settlement dedicated to or founded by St. Moluac of Lismore.” It would be difficult to imagine a more desolate place wherein a monk could experience what the Church Fathers call “the wretchedness of solitude.”

It is located on an almost completely flat landscape of stony, barely sowable land and rolling,deep, and treacherous peat bogs. During the winter months, fifty- and sixty-mile-an-hour bitingly frigid winds whip up clouds of stinging ice and snow. The dwellings of the monastic settlers were likely the stone beehive huts so characteristic of the other hermits throughout the outer Hebrides. The monks (if permitted a fire) burned peat to keep warm. Their living was mostly from the sea, upon which one could die at any time. Rains fell almost continually and storms blew up out of the sea in the twinkling of an eye and drenched the unwary traveler with sheet after sheer of rain. Sometimes the inhabitants were not friendly. One account tells of the inhabitants of one island being cannibals who had eaten the previous missionaries on the island.

Monk's cell and standing stone, Eileach an Naoimh, Scotland. Photo: Wikimedia

Synaxis of the Saints of Scotland. Photo: ancientfaith.com

1. St. Ninian and the beginning of Christianity in Scotland

The British Isles received Christianity from the very beginning, but the Christian influence was primarily limited to the area along their southern and southeastern shores, that is, those lands which had been colonized by the Romans. Those lands that had not been colonized, such as Scotland and Ireland, received Christianity a few centuries later.

The first of the great missionaries to Scotland was the fifth-century British bishop St. Ninian (Sept. 16, 432). He was spiritually and monastically formed by St. Martin of Tours (Nov. 11, 397) in the monastery of Marmoutier in Gaul (France) before heading to the southwest shore of Scotland. St. Bede of Northumbria (May 27, 735) wrote of him: “The southern Picts are said to have abandoned the errors of idolatry long before this date and accepted the true Faith through the preaching of Bishop Ninian, a most reverend and holy man ofBritish race, who had been regularly instructed in the mysteries of the Christian Faith in Rome. Ninian’s own episcopal see, named after St. Martin and famous for its stately church, is now held by the English, and it is here that his body and those of many saints now lie at rest. This place is known as Candida Casa, the White House [Whithorn], because he built the church of stone, which was unusual among the Britons” (St. Bede, Ecclesiastical History of the English People).

Before his death St. Ninian trained many great and holy men, one of the greatest of whom was St. Enda of Aran (March 23, 530). After spending some time at Whithorn, St. Enda returned to his native Irelan and founded a monastery on the Aran Islands. Many of his disciples went on to found monasteries I Ireland as well, such as the angelic St. Kieran of Clonmacnois (Sept. 9, 545) and St. Finian of Clonard (Dec. 12, 549).

St. Finian’s Clonard monastery in Ireland was to spawn the “Twelve Apostles of Ireland,” among whom were many who would later go into voluntary exile for the sake of Christ among the islands of Scotland and beyond, simultaneously bringing the Gospel to her peoples. In this way, the Gospel talent that St. Ninian invested in St. Enda was returned to Scotland a hundredfold through St. Finian’s disciples, such as Sts. Brendan of Clonfert, “the Voyager” (May 16, 577), Comgall of Bangor (May 11, 603) and, of course, the great Columba of Iona (June 9, 597).

2. The white martyrdom of the Irish monks

Christianity had already entered quietly into Ireland in the late fourth century. Yet when St. Patrick (March 17, 451) and St. Enda of Aran brought monasticism to Ireland, Christianity spread across the country like a forest fire raging out of control. The passions of the fierce-tempered, beauty-loving Irish soul were redirected in their proper direction – the heavenly kingdom. This resulted in hundreds of thousands of spiritual warriors who strove to “seize the kingdom of heaven with violence.” And truly they did “take it by force” (cf. Matthew 11:17).

By the beginning of the sixth century almost all of Ireland was ablaze with Christianity, and sparks were issuing forth from the blaze. These sparks were initially those rnonks who went on “pilgrimage for Christ,” who consciously abandoned their homeland and sailed off to the north and beyond in search of a “desert in the ocean.” The Irish monks called this desired location “the place of one’s resurrection” – that is, the place where God had called them to labor, to die and be buried, and from which to arise at the Last Judgment.

The Irish loved their country in a way that few can understand today, and for them to leave their beloved homeland produced a constant agony similiar to what unwilling immigrants to America felt. For an Irishman to consciously abandon his homeland for the sake of Christ we akin to a long, drawn-out martyrdom. A late seventh-century Irish monastic document known as “The Homily of Cambrai” does, in fact, describe such a sacrifice as “white martyrdom”:

“There are in fact three kinds of martyrdom, which we may regard as types of [carrying one’s] cross in human eyes: namely, white martyrdom, green martyrdom, and red martyrdom.

“A person undergoes white martyrdom when he leaves all for the sake of Christ, even though this means fasting, hunger, and hard work.

“Green martyrdom is attributed to someone who through them – that is fasting and work – is freed of his desires, or undergoes travail in sorrow and penance.

“Red martyrdom is to be found in the sufferings of cross of death for Christ’s sake, as was the way with the apostles, because of the persecution of the wicked, and while preaching the truths of God.

“These three lands of martyrdom are to be found in those sinful persons who are truly repentant, who abandon their self-will, and who shed their blood in fasting and in manual labor for the sake of Christ.”

3. The lure of the desert

The Hermit's Cell. Photo: colmcille.org

Among the Irish monks who sailed to the north there were great missionaries, but most of them were in search of an abandoned, unknown, remote land where they could live a solitary life devoid fall contact with others and be alone with God. The first stops that these monks made in their eager northward sea journeys were the west coasts of Scotland and especially the islands further to the west off these coasts. These “Western Isles” of Scotland, also known as the Hebrides, came to be filled with these Irish ascetics and anchorites. While some of the Irish monks continued on their voyages north, others settled deeper into the country in search of solitude. And truly, even to the modern Orthodox pilgrim’s eyes, the wild, harsh, rugged, lonely, and beautiful mountains and cliffs, which tightly nestle bright green valleys and deep blue lochs between their highland peaks, are ideal locations for monastic quietude and ascetic endeavor: where one can seek out and cultivate the seed of grace planted within one’s heart at holy Baptism – the Kingdom of God (cf. Luke 17:21).

Nevertheless, it was the multitudes of uncharted, uninhabited islands far off in the Atlantic Ocean that exerted the stronger pull on the Irish monks throughout the centuries, drawing them further and further northward, away from their homeland. Over the next five centuries the Irish monastic sailors spread abroad to the north, to the east (to the Scandanavian countries and northern Russia) and to the west (to Iceland, to Greenland, and even to North America).

4. The monastic life of Scotland’s missionaries

The Teampull Mholuaidh or St Moluag's church at Eoropie, Isle of Lewis, Scotland. Photo: wikipedia

One writer has written: “To capture the atmosphere of the early Celtic missionaries, travel north to Ness on the Butt of Lewis [the northernmost island of the Outer Hebrides]. At Eorpaidh Tempull Mholuaidh is a Norse Christian foundation on the site of a Celtic Christian settlement dedicated to or founded by St. Moluac of Lismore.” It would be difficult to imagine a more desolate place wherein a monk could experience what the Church Fathers call “the wretchedness of solitude.”

It is located on an almost completely flat landscape of stony, barely sowable land and rolling,deep, and treacherous peat bogs. During the winter months, fifty- and sixty-mile-an-hour bitingly frigid winds whip up clouds of stinging ice and snow. The dwellings of the monastic settlers were likely the stone beehive huts so characteristic of the other hermits throughout the outer Hebrides. The monks (if permitted a fire) burned peat to keep warm. Their living was mostly from the sea, upon which one could die at any time. Rains fell almost continually and storms blew up out of the sea in the twinkling of an eye and drenched the unwary traveler with sheet after sheer of rain. Sometimes the inhabitants were not friendly. One account tells of the inhabitants of one island being cannibals who had eaten the previous missionaries on the island.

Monk's cell and standing stone, Eileach an Naoimh, Scotland. Photo: Wikimedia

In addition to these external labors, the monk had his daily regime and personal ascetic practices. One has but to read a little of the Irish monastic “Rules” that have come down to us to see the ascetic intensity, single-mindedness, and severity with which these monks pursued their goal. Yet they were not pursuing asceticism as an end in itself: they were seeking to enter into a deep relationship with the Source of all beauty and truth: Christ God.

This Christ-centered striving directly flowered in tremendous artistic creativity. The monks became “co-creators,” creating things beautiful because they had been fashioned in the image of Him Who is the Creator and because they had consciously developed an inner likeness to the Source of all that is, both heavenly and earthly. This can be seen in the carved Celtic crosses, manuscript illuminations, the beautiful “Litanies” and poems that have come down to us, but, most clearly of all, in the “Lives” of these saints. It is this spiritual beauty that today attracts the soul of Westerners.

5. St. Columba and Iona monastery

Born in Ireland in 521 and being of royal blood, St. Columba (or Columkille) was consecrated to God from an early age and trained in the monasteries of Moville, Clonard, and Glasnevin by their founders: respectively, Sts. Finian, who had been trained in Whithorn after St. Ninian’s death (Sept. 10, 579), Finian (of Clonard – see above), and Mobhi (Oct. 12, 545). After leaving Glasnevin after St. Mobhi’s death, St. Columba went on to found the monasteries of Derry and Durrow. He travelled as a missionary throughout his beloved Ireland for almost twenty years before voluntarily going on pilgrimage for Christ to the north. In 565 he settled on the island of Iona off the west coast of Scotland, where he remained for the next thirty-two years. While there, he brought about the conversion of many people along Scotland’s western shores.

St. Columba died on Iona in great holiness on June 9 in the year 597. After his death Iona continued to be the center for the spread of Orthodox Christianity throughout Scotland for the next two-hundred years, succeeding St. Ninian’s monastery of Whithorn as Scotland’s most influential missionary center. A vast number of saints blossomed from the island, but here we will name only a few: St. Eithne of lslay and Ailech (the mother of Columba), St. Ernan of ]ura (the uncle of St. Columba), St. Baithene of Islay and Tiree, St. Fergna, St. Segine, St. Cummene Ailbe, St. Adamnan and St. Bresal.

Iona’s great and far-reaching influence was abruptly cut short with the descent of the Vikings in the eighth century. Thus, Iona also became an island of martyrs, and the path of red martyrdom began on the islands of the western sea.

The Annals of Ulster record at A.D. 794: “The devastation of all the islands of Britian by the heathens.” The Annals of Inisfallen at 795 record “the devastation of I-Columkille.” The Annals of Ulster further tell how in 802 “I-Columkille [was] burned by the heathens” and in 806: “The community of I-Columkille slain by the heathens, that is, to the number of 68.” In 825 they record: “The martyrdom of Blathmac, Fland’s son, by the heathens in I-Columkille.” Finally, in 986 another murderous raid by the Vikings was leveled on Iona, and sixteen monks were killed on a northeast shore of the island now known as the “White Strand.”

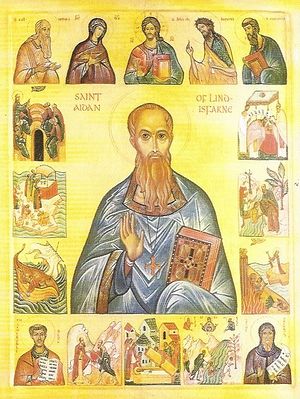

6. St. Aidan and Lindisfarne Monastery

The most famous spiritual offspring of the Iona monastery we the monastery at Lindisfarne, located on an island off what is now the far northeast coast of England. The history of this monastery is well told by St. Bede in his Ecclesiastical History, and the portraits of the founder of Lindisfarne, a monk of Iona named St. Aidan (Aug. 31, 651) and its most famous inhabitant, St. Cuthbert (March 20, 687), are among the most inspiring and beautiful Lives of Saints ever written.

The monastery of Lindisfarne became the main missionary center for England in the seventh and the eighth centuries. Many of its monks became missionaries and bishops who travelled throughout England. They converted many of the newly arrived Anglo-Saxon pagans, and, what is more significant, re-converted many of the pre-Saxon-invasion Christians who had lapsed to paganism out of fear or weakness. In this they had a more far-reaching success than St. Augustine of Canterbury (May 26th, 605), who had been formed in traditions that externally were foreign to those of the British Celts he was sent to. Thus, the work of some of St. Aidan’s disciples, such as Sts. Chad (March 2, 672) and Cedd (Oct. 26, 664) of Northumbria helped bridge the Roman and Celtic traditions and greatly complemented St. Augustine’s work and mission.

St. Aidan also encouraged women’s monasticism. He had several disciples who went on to become great and holy abbesses, including Sts. Bega of Bee (Oct. 31, 7th c.), Heiu of Tadcaster (Sept. 2, 7th c.), Ethelreda of Ely (June 23, 679), Ebba of Coldingharn (Aug. 25, 683), and Hilda of Whitby (Nov. 17, 680).

Lindisfarne itself; like Iona, fostered many saints – including Sts. Finan, Colman, Fintan, Eata, Felgild, Aethilwald, Eadberht and Eadfrith – and became an island of martyrs at the hands of the Viking marauders. In 793 the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle records: “On the sixth of the Ides of June the ravaging of the heathen men lamentably destroyed God’s church at Lindisfarne,” at which time some of the monks were stripped and tortured. In 801 the Vikings came again and tried to put what remained to the torch. Finally, in 806 the Vikings slew about eighty monks who were still dwelling on the Holy Island.

7. An age of heroism

One of the most lasting qualities of the saints of Scotland over the centuries has been the air of heroism that filled their lives and deeds. They sailed off into unknown territories and faced perils both physical and spiritual with a bravery and steadfastness of soul that the warriors in the service of earthly rulers (particularly in the West) would stand in awe of and strive to emulate in succeeding centuries.

These saints were true spiritual warriors whose lives and deeds have a power to exalt the soul. Written in a way that is “larger than life,” their Lives almost involuntarily lift one (especially the Western reader) out of the chokingly small-mindedness and stinginess of soul that often characterize our daily lives. Directing the inner eyes of the attentive reader to the freedom, breadth, and grandness of living a life of self-sacrifice in carrying one’s cross, these saints can impress on one’s heart the reality of the living Christ, making him yearn to be consumed by the fire of His grace, His beauty, and His love.

These were men and women who deliberately went into solitude to enter into open spiritual combat with demons after many years of repentance, patience, and humility, being prepared in spirit by the grace of God for such labors. Many of the Church Fathers, who had extensive personal experience in these realms, write of the impossibility to describe all the wiles and cunning that these unseen enemies use against the soul.

Yet the Fathers say that it is likewise just as impossible to describe all the blessings and fruits of the spiritual victory that God accomplishes in one to be victorious in battle. Often the Fathers describe these blessings in poetic terms, telling of the mysterious, unseen activity of God’s grace that takes place in the hearts of the saints and that is the potential inheritance of all Orthodox Christians.

May the newly born seedlings of Orthodoxy in the West come to know and treasure their own spiritual heritage more fully, entering into its essence step-by-step through the carrying of one’s cross in patience, humility and love of God and neighbor. Amen.

From the St. Herman Calendar, 2001

Monk Nicodemus (Jones)

2/5/2019

Δεν υπάρχουν σχόλια:

Δημοσίευση σχολίου